The “burning platform” story has become a permanent part of the organizational change landscape. In this series, our guest author Daryl Conner offers some background about how he found and introduced the story, what its original purpose was, how that intention has sometimes been misunderstood, and some of the implications for change practitioners who incorporate the metaphor into their practice.

With the previous three posts as a foundation, the following implications may be helpful for change practitioners who wish to use the burning-platform metaphor in their work.

1. When real burning-platform urgency is at hand (due to either current or anticipated problems or opportunities), it means people believe the penalty for not realizing the intended outcomes is significantly higher than the investment for doing so.

- Current problems attract attention more easily but they usually provide only limited options. When the flames are imminent, people will be highly motivated to change. At that point, however, there is usually only enough remaining time and resources for tactical moves—there’s no room left for strategic maneuvers.

- Anticipated opportunities are the hardest to convince people to accept because it often looks as if something is being fixed that isn’t broken. However, this is where strategic breakthroughs are made if people do get on board.

- Timing is important. If commitment to leave the status quo forms too early, it won’t be sustained; if it develops too late, it won’t have an impact.

- With true business imperatives, commitment is inevitable…the issue is whether the determination to take action will come forward in time to be meaningful.

2. The story isn’t about fear, it’s about resolve—the fortitude and steadfastness to no longer pay what has become or will become an inordinate price for the existing conditions.

- The fact that a burning-platform-type situation is scary doesn’t mean fear is at the heart of the unfolding dynamics. The focus is on an unwavering determination to depart from existing circumstances.

- Fear is a symptom, not a cause, of a status quo too expensive to maintain. The primary attributes associated with a burning-platform mindset are courage and commitment, not terror and panic.

3. We should encourage clients to avoid the two most common misinterpretations:

- The metaphor is not meant to imply that major change requires immediate, catastrophic consequences in order to be successful.

- The metaphor is not meant to imply that leaders should intentionally manipulate information or circumstances to manufacture the appearance of urgency for change when that’s not actually the case.

4. The resolve to change doesn’t reach burning-platform status until leaders feel deeply committed at an emotional level to its realization:

- If leaders feel their personal brand is at stake (their own sense of mission, self-worth, values, legacy, honor, reputation, ethics, etc.), they are more likely to do everything within their power to reach realization.

- Burning-platform steadfastness goes beyond intellectual acceptance, so it can’t be synthetically manipulated or coerced. This kind of attention and diligence can be discovered within oneself and strengthened, but it can’t be effectively contrived or feigned.

5. The function of a burning platform mindset isn’t just to break from the past; it also serves as a deterrent to backsliding into previous habits and routines.

6. The “burning platform” term is used far too often, which dilutes its impact:

- In some companies, it has become synonymous with anything anyone thinks is important to accomplish instead of the absolute top-priority change initiatives that leaders have declared essential to realize.

- If the term is applied too liberally, it’s easy to overload an organization with too many initiatives to be absorbed all at once. Successful organizations prioritize their initiative portfolio so that only a few are designated business imperatives at any one time.

- When this happens, the changes in play are usually installed rather than realized—in addition, productivity, quality, and safety standards typically begin to falter.

- Designating an initiative as a burning platform must be done within the context of the other changes under consideration. An initiative can only be seen as a business imperative compared to the other projects that are competing for attention and resources.

7. When involved in developing implementation architecture, the change practitioner’s role isn’t to create pain and hope; it’s to help clients uncover, articulate, and leverage the pain and hope inherent in what they are attempting to accomplish.

8. Both PM (how the pain of maintaining the status quo is expressed) and VS (how hope for a better future is fostered) are vitalto reaching realization:

- There are two prerequisites for successful transformational change:

• Pain comes from the information that justifies breaking from the status quo.

• Solutions are desirable, accessible actions that solve a problem or take advantage of an opportunity.

- Together, pain management (PM) and viable solutions (VS) represent foundational aspects to change architecture. PM provides the motivation to pull away from the present; VS provide the motivation to proceed to the desired state.

- Part of why the burning platform story became so popular is that, without an expensive status quo, the cost of transformation is unlikely to be paid.

• For this reason, at the beginning of the execution process, both PM and VS are reflected in communications, but it is PM that takes center stage.

• As the implementation unfolds, more emphasis should be placed on VS, yet the weight on PM should not decrease.

• Once critical mass of commitment has been reached, PM can be de-emphasized with a stronger focus placed on VS - Our role as professional change facilitators puts us at the forefront of either fostering or impeding the explicit use of PM by leaders. As such, our own acceptance or rejection of the need for PM is pivotal.

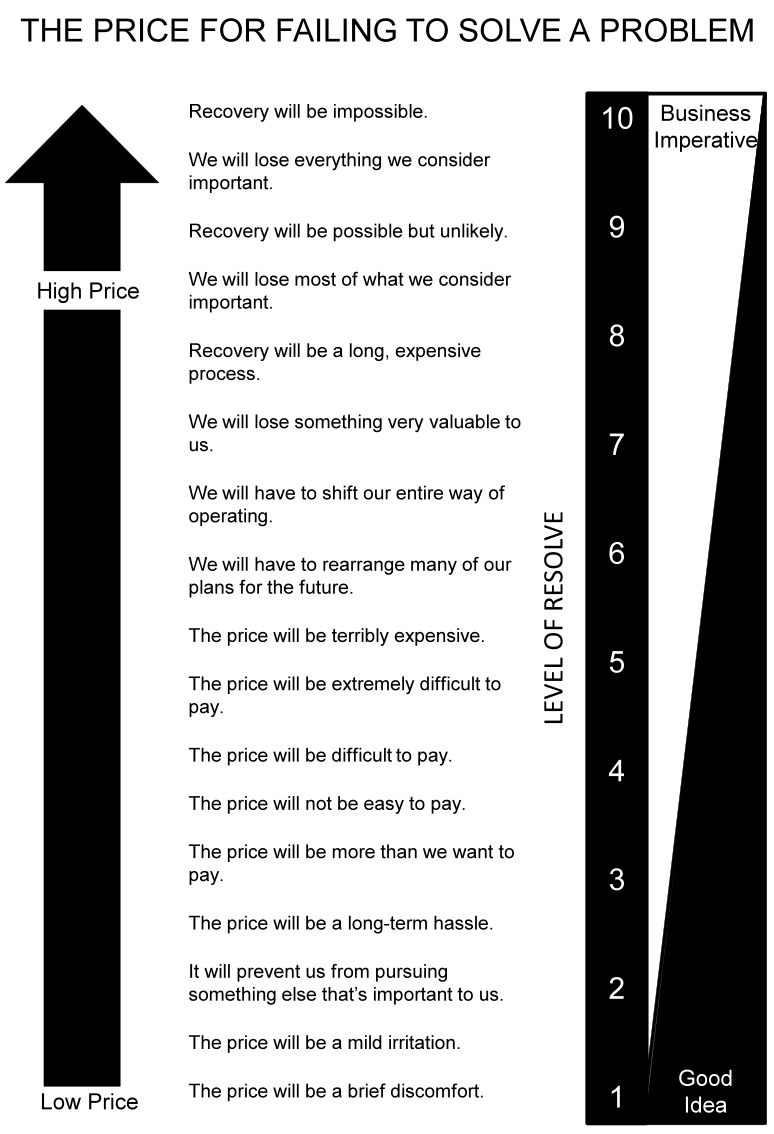

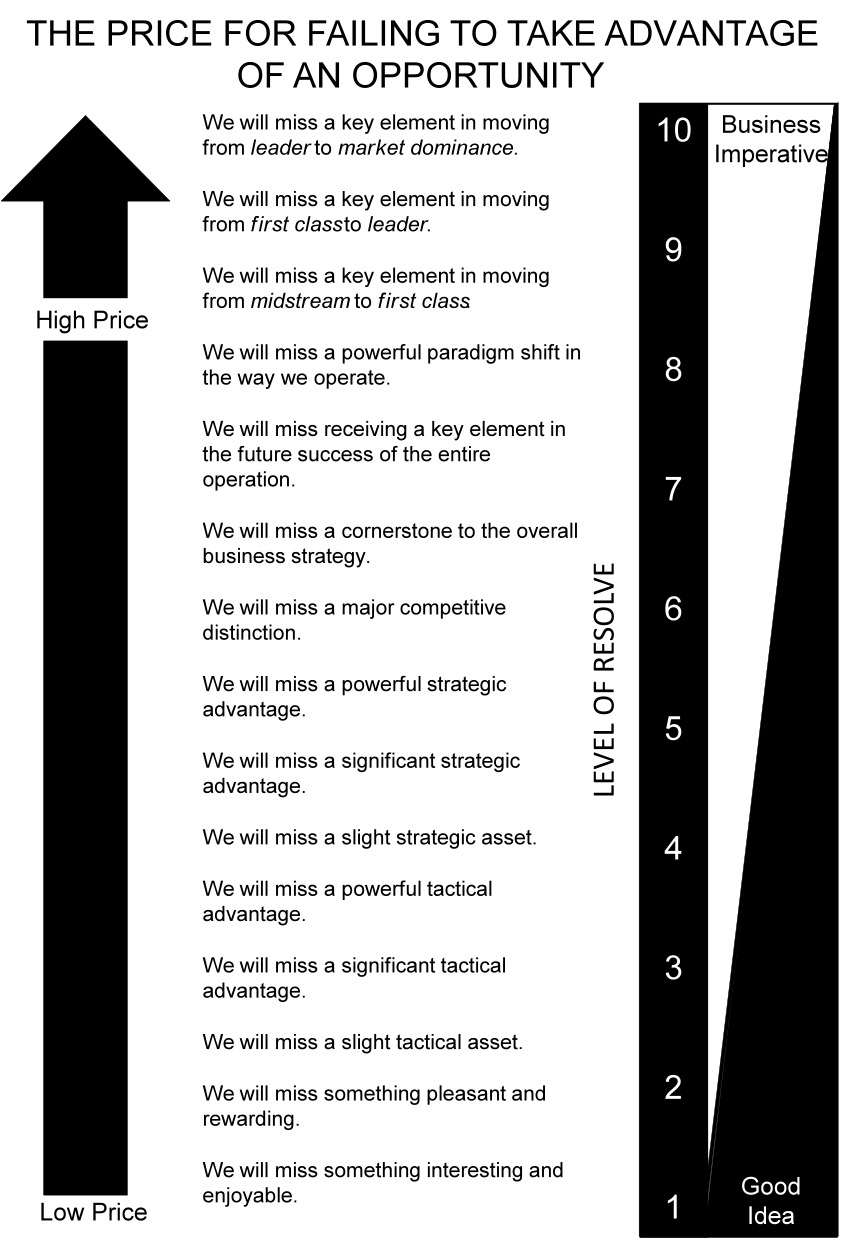

9. It is essential to distinguish good ideas from business imperatives

- Good ideas are initiatives with solid reasons for being pursued (could make money, delight the customer, keep up with the competition, the shareholders would be happy, etc.). Business imperatives are initiatives that would be too expensive not to pursue. A good idea has all the earmarks of something worth trying…a business imperative is a non-negotiable, “must get done” endeavor that has to succeed no matter what the obstacles. With good ideas, you give it your best shot…with business imperatives, you are “all in”—everything at your disposal is utilized to ensure realization is reached. Good ideas are primarily rationally based. (“It just makes sense to see if this can work.”) Business imperatives have a solid logic behind them but they are also emotionally based. (“I won’t be able to justify it to myself or those who depend on me if we fall short of the mark.”)

- Figures 1 and 2 provide some examples of the price of unresolved problems or missed opportunities. The items at the lower end of each scale represent good ideas. Moving up the scale, the costs shift to business imperatives—those that are too expensive to pay for and absolutely must be resolved.

- Each leader and organization has a different tipping point for where a good idea becomes a business imperative. Based on variables like assigned duties, interpretation of relevant information, the nature of the change, and one’s tolerance for risk, sponsors may vary widely as to when they declare that an initiative constitutes a burning platform. One leader may view a level 3 or 4 problem/opportunity as a change that absolutely must be fully realized, while another may face a level 8 or 9 situation and still not interpret it as an absolute must to accomplish at all costs.

The burning platform metaphor describes the commitment needed to sustain movement away from unacceptable conditions, whether they are current or anticipated problems or opportunities. It also describes the tenacity needed to break from the past and counter the inertia that holds people inside their zone of familiarity. Pain is not the only motivator for transformational change, however. Hope for a brighter future can also fuel the engine of deep, sustainable change. The common denominator for both is that the implications for continuing the status quo are too much to endure. For this reason, the story is meant to highlight the importance of resolve (not peril) when leaders strive for full realization of their change initiatives.

When I first introduced the metaphor nearly 25 years ago, my aim was to help people understand the role commitment plays in successful change. Here, I’ve attempted to clarify some misconceptions so practitioners can use the story to help leaders confirm and express their own resoluteness toward change, and be better prepared to help others further down in the organization invest the same level of commitment.

Series Navigation

<< The Four Kinds of Burning Platforms

Pingback: Implications for Practitioners Using the Burning-Platform Metaphor | Reply-MC | Organization Design and Transition | Scoop.it()