The “burning platform” story has become a permanent part of the organizational change landscape. In this series, our guest author Daryl Conner offers some background about how he found and introduced the story, what its original purpose was, how that intention has sometimes been misunderstood, and some of the implications for change practitioners who incorporate the metaphor into their practice.

When something goes viral, it’s seldom a deliberate act to distort the original meaning. Nonetheless, the message almost always changes to some extent. It’s a natural consequence of thousands of people selectively hearing, remembering, and communicating to others what they understand to be true. I believe that when the burning platform story’s meaning was twisted from my original intentions (see my last post), it was primarily because the scorching oil rig and Andy’s leap into the water are such compelling images. The reason I selected the story was that I thought it would be memorable. To say the least, it has proven to be that.

The abandoned shell of twisted, burned steel that was once a center of activity for more than 200 oil workers is a powerful testament to the fierce intensity of the devastation that took place. Unfortunately, some people only registered and passed on to others the specifics of that particular event (a do-or-die situation), and not the broader implications I wanted to highlight when I chose this as a metaphor for commitment.

Clearly, one of the reasons behind the persistence of the two primary burning platform misconceptions I mentioned in the last post is that Andy’s situation was such a life-threatening event. The mental picture of him jumping, and the associated emotions it evokes, are a formidable blend. When people remember or retell the account, they sometimes forget that the story was meant as a placeholder for a larger point (the depth of commitment needed for major change). In addition, many people associate important change with problems. (“The only time we change around here is when something needs to be fixed.”) The forceful imagery evoked from the story, combined with the association people tend to make between impending danger and the need to alter the status quo, is compelling.

Although I’m pleased so many people remember the story and have gone to the trouble to share it with others, my hope is that this series will reframe the crisis-centered interpretation sometimes attributed to it. Contrary to how some people relate to the term “burning platform,” I don’t see it as a story of disaster. To me it’s a tale of courage and tenacity that illustrates the commitment necessary to face the risk and uncertainty inherent in departing from the current state of affairs.

I never intended to give the impression that an emergency was always necessary to motivate sustained major change. If one word is associated with the story, I would prefer it be resolve rather than peril. People don’t have to face a life-threatening situation or organizational insolvency in order to support fundamental change. What is required is a deep level of resolve: the determination, fortitude, and steadfastness to stop paying what has become or will become an inordinate price for the existing conditions.

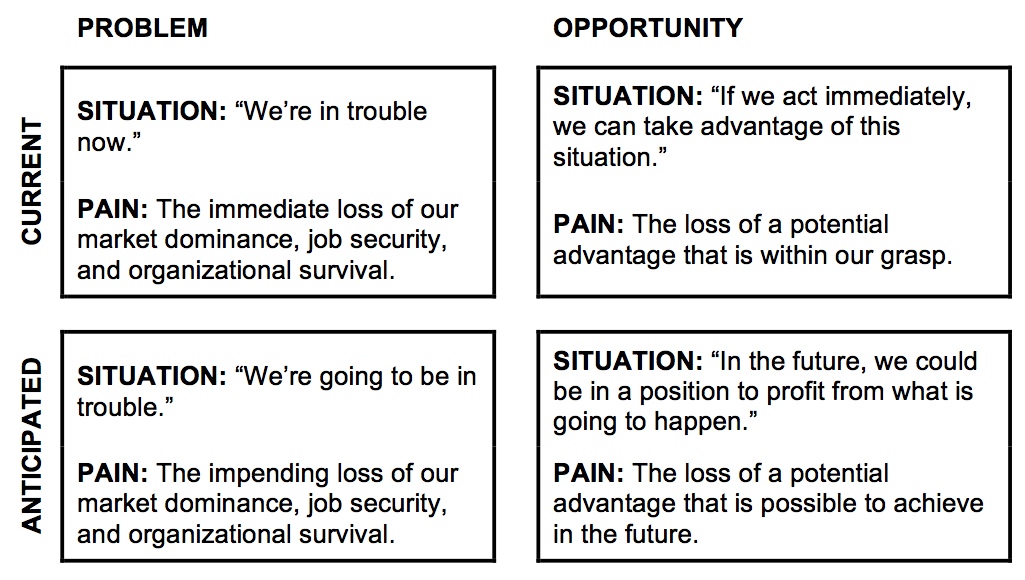

When the implications for not changing far outweigh what it will take to realize the desired state, this kind of profound determination will play itself out in four ways:

- Current problems

- Current opportunities

- Anticipated problems

- Anticipated opportunities

I’ll describe each in more detail below, but, in general, think of these as four motivations for changing at a fundamental level. Although it is important to distinguish between these four origins of deep commitment, as far as the metaphor is concerned, the real issue isn’t the motivation driving the change, it is the level of determination demonstrated for leaving what is for what could be.

Someone who displays a genuine burning-platform mindset won’t approach the situation as if finding a remedy is “nice to have” or even something highly desired. A sponsor who demonstrates the kind of commitment the metaphor depicts views change success as non-negotiable. He or she will treat it as an absolute business imperative to achieve the intended realization outcomes. The price for the status quo makes succeeding with change a very personal thing…“Nothing can stand in our way—this initiative must reach its intended outcomes.”

Current Problems

The result of maintaining things as they are in a burning-platform situation inflicts a grievous cost. Andy’s plight represents circumstances that epitomize a current problem—when people determine that leaping into the scary unknown is expensive, but less so than the costs they face if they continue with things as they are. By no means, however, is this the only reasoning that supports fundamental transformation.

Anticipated Problems

The second set of conditions that will cause people to leap into frightening change is anticipated problems. Here, existing circumstances don’t reflect an immediate threat, but a trend or some type of projection into the future strongly suggests that the situation will deteriorate significantly if the current course is maintained. Major change that is based on problems that are likely to emerge or get worse, but haven’t yet done so, is less common than immediate problem-driven transitions, but it most certainly does occur. For example, maybe Andy could have prevented the explosion or at least made a more orderly and safer evacuation if he had known about and been in a position to act on the problem before things got out of control.

Either way, dramatic change is fairly uncomplicated when people are solving a problem, current or anticipated. That’s not to say it is necessarily a picnic when it comes to all that is involved in reaching full realization, but trouble-centered change is relatively straightforward to justify and generally easy for people to relate to.

Current Opportunities

With the third burning-platform circumstance, the issue is still the high cost of the status quo, but here, maintaining the needed resolve can be particularly challenging. Getting excited about wonderful new options is the easy part. It’s staying the course when implementation becomes protracted and/or difficult that people have trouble with. It’s usually much harder for people to sustain their commitment to change when pursuing current opportunities than it is when they are trying to solve problems.

Despite this tendency, we have all witnessed people who initiated a shift in something fundamental because of their desire to upgrade their status. They got married, had children, completed an additional level of education, accepted a promotion, expanded market share, increased shareholder value, introduced new technology, etc. Current opportunities offer a favorable harvest that can be enjoyed immediately and thus represent a strong early motivator for change. The question is, will that motivation persevere throughout the implementation process?

Once again, the key is the price that will be paid if the change is not successfully realized. Only when failure to exploit the opportunity becomes too costly will positive situations be just as galvanizing toward change as the more negative-based motivators.

Anticipated Opportunities

Finally, anticipated opportunities are situations where the benefits of leaving the status quo can only be savored later. Here, burning-platform commitment is tied to the implications faced if the desired advantage is not achieved in the future. This can be a very powerful motivator for change, but securing substantial, lasting commitment under these conditions can also be extremely difficult to achieve. The challenge is not only that the change is being driven by opportunities exploited instead of problems resolved (I’ve already outlined how this can make implementation challenging), but the potential for gaining the desired advantage resides in the future and is easy to defer.

Whether they are current or anticipated, opportunities must be extraordinarily attractive to spur the sustained effort implied in business-imperative situations. The lure must be so powerful that the person feels that the price for not attaining the goal is beyond his or her ability and/or willingness to pay.

Be Careful

A word of warning to change facilitators. The opportunity side of burning platforms can be tricky. Grasping how a positive future can be linked to the pain of the status quo can sometimes be easier said than done for clients.

This is where the reframing skills of the practitioner play an important role. Part of what we do for clients includes helping them see that sometimes opportunities left unleveraged can produce just as many negative implications as unresolved problems. It doesn’t matter if there are expensive difficulties that need resolution or wonderful options that would be painful if not taken advantage of. Either way, continuing with the present course of action is no longer an option.

Maintaining the Status Quo

I hope this explanation of the four conditions that constitute burning platform situations helps you see that the crisis Andy faced is only one version of the kind of resolve the metaphor was meant to describe. Yes, some leaders do enter into a burning-platform mindset because of current do-or-die circumstances, but others successfully pursue change with the same steadfastness based on problems they know will surface down the road. Some sponsors have been able to convince their organizations of the necessity for paradigm-level change because of existing or forecasted benefits that lay in the future. Whether the situation is about current or anticipated problems or opportunities, the common denominator in each case is an unwillingness to continue supporting the way things have been.

It’s All in the Timing

The conviction to depart from current circumstances can surface early or late in the implementation process. When the resolve forms early, a company has anticipated what the price or pain of the status quo will be if the desired action is not taken. When the resolve develops late, there is already a price being paid that is too expensive to bear.

Current pain is what inspires commitment to change late in a situation. Unfortunately, most of the time, only short-term tactical actions are possible at that point. When the resolve to change comes early, it is due to anticipated pain. Anticipated pain can be more powerful due to the extra time available in which to make strategic moves. This kind of change is often more difficult to convince people to act on, however, because they tend to stay caught up in the crisis du jour.

If the decision to leave the status quo forms too early, it won’t be sustained; if it develops too late, it won’t matter. When burning-platform situations are at hand, the issue isn’t will the necessary commitment to act be generated, but when. With change that is truly imperative, commitment is inevitable…the crucial variable is whether the determination to take action will come forward in time to be meaningful.

The Focus Is Resolve, Not Peril

The burning-platform story is about having the tenacity to do whatever is necessary to no longer pay for the prohibitively expensive status quo. When change initiatives are propelled by interest of a less intense nature, they are considered “good ideas,” not “business imperatives.”

Because of the importance placed on predictability, when there is a dramatic departure from the status quo, people always struggle with the transition (even when they desire the outcome) . In fact, the only way the gravitational pull of “the way things are” is broken is when the price of the status quo becomes prohibitively high. If the motivation for leaving present circumstances is based only on intellectual interest or even a strong preference, the likelihood of a successful implementation is low. Moving away from established patterns of thought and behavior is unlikely if what is in place is only moderately costly (dysfunctional).

When executing major initiatives, leaving what is for what could be doesn’t often occur unless the existing conditions have become unbearable. It is then, and only then, that change becomes a non-negotiable priority. Said another way, for significant change to reach realization, the people involved must be more than merely intrigued by the idea of departing from what they are doing (good idea); they have to reach a point where their resolve to change is tenacious and unyielding (business imperative). For example, a burning platform mindset is in play only if leaders move beyond relating to their initiative as an organizational commitment and start seeing it as a promise they have made to themselves and others. It must become personal; they must feel their own credibility and integrity are at stake.

In the next post, I’ll talk about the relationship between pain and hope, which are both necessary to create the commitment needed to sustain transformational change.

Pingback: The burning platforms of my life | Keeping up with the Walkers…()