In the third and last post of this series I address the conciliation of the ideal situation and what usually happens, because bringing the two situations together gives us a surprisingly accurate answer to the initial question: When is it time to go? As a bonus I include three conversation starters to nudge our customers in the right direction.

I started this series with the statement that we should discuss the end of an engagement upfront with our clients, even before any contract is signed. The end state should not be the delivery, but the community that is built around it. Now that I am at the last post in this series I’m starting to realize that this is a bold statement with far-reaching implications on multiple levels:

- The customer relationship leaves more room for vulnerability, honesty and candor.

- The customer expectations about our role change from being a supplier of services to being a capacity builder for the community around the project.

- The design of the program includes concrete steps to build a social architecture at the same pace as the delivery of the technical architecture.

- The delivery of the program is done in co-creation with that community.

- As a result, at the end of the program we will have a higher chance of reaching the commitment that is necessary for the organization to continue the effort.

As a comparison to the ideal world, I used the second post of this series to explain what our projects usually look like. They start off pretty much the same way with the delivery of expertise. Soon after that we discover that there is no plan to adjourn, so the next best option is to perpetuate the dependency we have just created. I referred to this as ‘the stinking problem of dependency’.

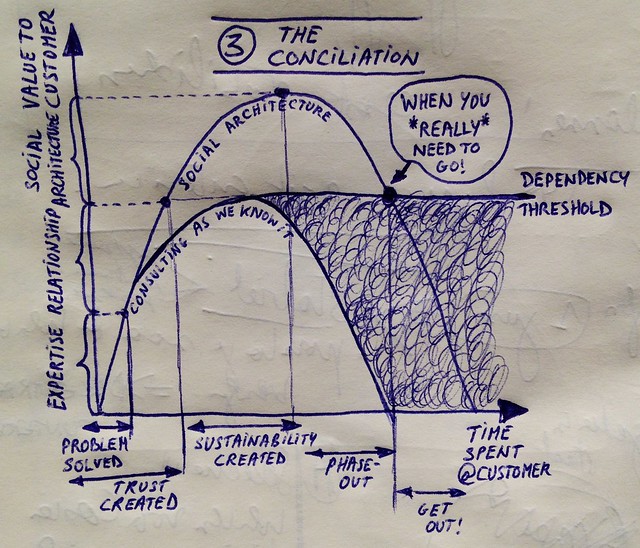

On the graph below I have combined the two approaches: the first is the curve of ‘Social Architecture‘, the second I have nicknamed ‘Consulting as we know it‘.

One thing that will immediately strike you is that the Social Architecture curve covers a longer period of time and reaches a higher level of customer value. The customer value on the vertical axis has three parts: the value of our expertise, the value of our relationship, and the value of the social architecture we leave behind.

Keep the focus on that vertical axis for a second and ask yourself what the value for the customer is of investing time and resources into the relationship level after the delivery of the expertise according to the specifications… In the case of ‘Social Architecture’ this investment serves a purpose: the construction of a social fabric. In the second case I am afraid that it only serves to sell more dependency around the solution.

Investing in relationship management without envisaging Social Architecture is like flying first class: the journey is more comfortable, but the destination remains the same. Instead of the plain delivery of expertise, the service gets topped with after-care, audits, analysis… and random acts of heroism that serve the perpetuation of the victim-rescuer dynamic. That is why the two curves have different slopes on the relationship level.

[Conversation starter] Customers should ask themselves: ‘Why are we investing in a relationship with a certain practitioner?‘ and ‘What is the return of that investment?‘

Next, let’s have a look at the horizontal axis. We can see that the time it takes to solve the original problem is pretty short in comparison to the time that it takes to develop a community around the solution. When the highest point is reached on the ‘Social Architecture’ curve, we see that the added value of the other curve has already dropped below the dependency threshold.

[Conversation starter] Customers should ask themselves: ‘Which curve are we on?‘ and ‘Did we hire an expert or a social architect?‘

When the summit is reached on any of the two curves it is time for a practitioner to go. But rather than talking about a specific point in time, I would rather talk about a take-off slot, which is visualized on the horizontal axis as ‘phase-out’. This is what I would call a reasonable time to say goodbye. As a code of ethics we should vow to ourselves never to stay longer than the dependency threshold (see: ‘get out!’ on the horizontal axis).

[Conversation starter] Customers should ask themselves: ‘Where are we on our curve?‘ and ‘Is it already time to say goodbye?‘

So there it is; the answer to the original question “When is it time to go?”: it’s a take-off slot, but it takes a different conversation in order to locate it on our project timeline!

As a result of this blog series I have distilled three kinds of conversations (blue boxes above) that are worth having with the customer. These are the conversation starters that can deepen the customer relationship … and increase the client effectiveness.

Series Navigation

<< When is it Time to Go? (Part 2)