When we make customers dependent on our expertise, we create stinking dependency. The problem is that we solve the problem, without treating the root-cause.

And when somebody knows you well

Well, there’s no comfort like that

And when somebody needs you

Well, there’s no drug like that

(Heather Nova in London Rain)

In the previous post I raised the question of when it is time for a practitioner to end an engagement. I suggested that the delivery of our expertise is only the entry ticket. Eventually, our real added value lies in the deployment of a Social Architecture that allows the customer to be self-sufficient in sustaining the effort. Unfortunately, Social Architecture is the road less traveled. Therefore, in this post, I will zoom in on what the situation looks like in the majority of our engagements; i.e.: when we stick to doing what we were asked to do: being an expert and solving the problem.

This is how it usually goes: we enter into a contracting phase where the assignment is discussed, the timeline and the deliverables. It’s the closing of a deal. What we often neglect at that point are the benefits and the life after the delivery. Compare it to a mother who is only interested in giving birth, but not in having a child.

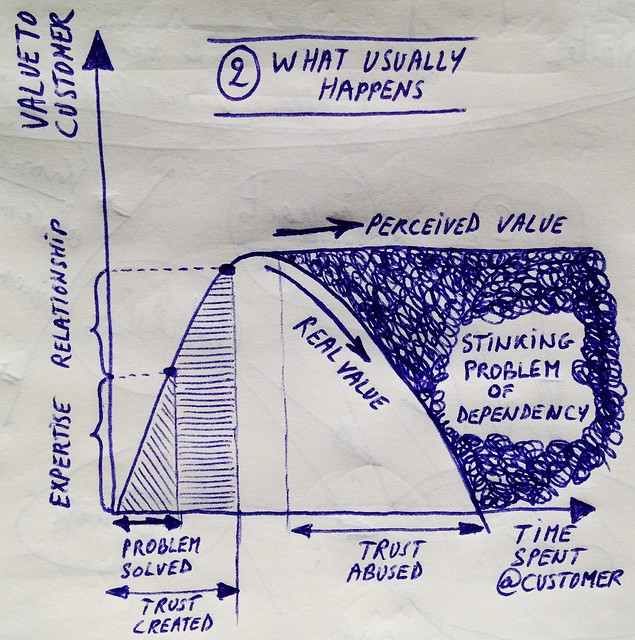

From the graph below you can see that the value we add for our customers increases our value, and even if we stay a little longer after the delivery (for example to do the after-care, post-analysis, auditing, optimizing, etc.) our value still increases. It’s the polishing of the solution. After that, there is no plan, … or is there?

Logically speaking, the top of the curve is the cut-off point where such engagements should be ending. Unfortunately, this is where it goes wrong in 99% of the cases. As the contracting phase was limited to the closing of a deal, no agreements were made about sustaining the solution in the long run. Sure enough, ‘knowledge transfer‘ and ‘documentation‘ may be part of the journey, but they carry the same value as an obstetrician handing over an encyclopedia to the mother on the last appointment.

And here is the perversity of our profession: instead of navigating towards independency, we see customers and practitioners diving into a victim-rescuer dynamic. The perceived value of our interventions remains high, but in reality we have tipped over into being a hired hand. There are several reasons why I talk about a ‘stinking problem‘ in such cases:

- The victim-rescuer dynamic produces a cycle of ad-hoc urgencies and heroic acts. This cycle is symptomatic and functions as a self-fulfilling prophecy in that it confirms over and over that the interventions are necessary. Aren’t we lucky to still have the experts on board?’. While being unethical for both, the client and the practitioner, this dynamic is only the visible part of a far more brutal truth, i.e.:

- The initial cause of the problem isn’t solved. The simple fact that we restrict to doing what we were hired for (solving the problem), often implies that we neglect to talk about the root-cause and to have a conversation on the conditions that should be met in order to sustain a solution in the long run.

- Relationship management is being (ab)used for creating recurring business, instead of building a Social Architecture. Instead of building and strengthening the social fabric of self-sufficiency, the time spent at, and with the customer is filled with conversations that only serve the perpetual victim-rescuer dynamic.

It’s sad to conclude that the perpetuation of the victim-rescuer dynamic is abundant (and taken for granted). But there is another path, provided that we have the guts to bring it up even before the contract is closed.

In the next and last post of this series I will talk about the conciliation of the ideal situation and what usually happens, because bringing the two situations together gives us a surprisingly accurate answer to the initial question: When is it time to go?

Pingback: When is it Time to Go? (Part 1) | Reply-MC()

Pingback: When is it Time to Go? (Part 3) | Reply-MC()