In this article I want to pick up the broken pieces that resulted from my organizational culture rant of an earlier post. I stated that measuring culture is the wrong pot to piss in.

Well, not in those exact words, but I did meet some HR managers who were not too happy about the directness. In contrast to that particular article, I now want to focus on how to approach organizational culture. More in particular, I argue that philosophy and not psychology holds the keys to organizational culture.

Doing Versus Being

Without getting too philosophical we should note that the way you are being is the source of your reality, which in turn is the source of your actions. But the domain of being is hidden because it is not referred to in everyday action oriented language. ‘Being denies its own coming into existence’, as Martin Heidegger notes.

The point is that changing an organizational culture is creating something that is currently not possible in your reality. It is not improving something that is now already possible in your context by making it better, different or more (which is the domain of DOING). Instead, it is exchanging the current context for a new one in which certain things all of a sudden become possible (context is the domain of BEING).

Again the key insight comes from the philosopher Martin Heidegger. According to him, language is the only leverage for changing the world around you. This is because people apprehend and construct reality through the way they speak and listen. In her book The Last Word On Power, Tracy Goss continues Heidegger’s statement. According to her, by learning to uncover the concealed aspects of your current conversations and learning to engage in different types of new conversation, you can alter the way you are being, which, in turn, alters what’s possible.

The Anatomy of our Perception

In the previous article on culture I ended by saying that hat our inability to measure culture does not prevent us from creating one. But first, let us have a look at what it is made out of. As you remember, culture is a sense making mechanism that works like a pair of glasses you are wearing. It determines your perception, i.e.: the data you select.

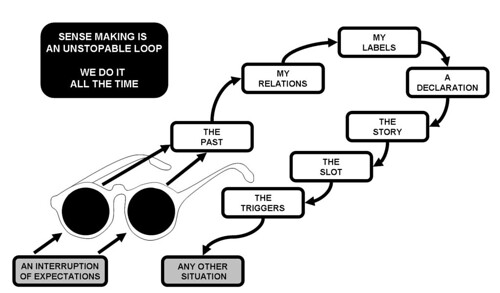

Sense making is hard-coded into all human beings. It is something we do all the time (you can not ‘not do it‘, like it is impossible to ‘not taste’ the food that is in our mouth) and it always follows the seven steps that are derived from Karl Weick’s seven characteristics of Sense Making in organizations:

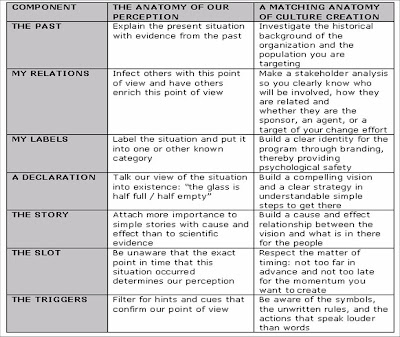

1. The Past: We make sense of our experiences by comparing them with previous experiences. The organizational past is an important indicator in predicting the reaction to the current organizational change. The past is something that comes walking in through the back door of emotions. People remember events that have the same emotional tone as what they currently feel. Past events are reconstructed in the present as explanations, not because they look the same but because they feel the same.

2. My Relations: We make sense of changes in organizations while in conversation with others, while reading communications from others, and while exchanging ideas with others.

3. My Labels: People are sense-making creatures. Whenever a change happens that affects us we give it a label and put it into a known category (dangerous, stupid, beautiful, etc.). Almost instinctively, we respond with familiar questions: Who is behind this? What are the credentials of those people? Who said so? What will become of us after that change? Do they have the support of management?

4. A Declaration: Words have consequences. We should never underestimate the power of words and conversations. A situation is “talked” into existence, and the basis is laid for action to deal with it. Declarations are the way we translate stuff from below the surface into explicit knowledge. As a simple example, when people constantly say that “this project stinks” they create a climate in which the observation of difficulties is stimulated and the observation of possibilities is constrained.

5. The Real Story: People are interested in the truth, not the details. And people are not stupid. We construct the meanings of things based on reasonable explanations of what might be happening rather than through scientific discovery of “the real story.” Here is a warning flag to heed at this point: What is a simple truth for one group, such as managers, often proves implausible for another group, such as employees.

6. The Timeslot: Sense making is linked to timing. Like an airplane waiting for takeoff, an event will only get a limited slot for takeoff in the attention span of an individual. If that moment of attention happens to be the right one, it helps in setting a culture.

7. The Triggers: Nobody is capable of observing it all. Our observation is based on extracted cues. The cues that we observe depend on what we expect to observe, As a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, we shape our reality according to how we expect it to be. When we think we are going to succeed at something, we will be triggered by every cue that confirms this reality and act upon it, and vice versa.

The Anatomy of Culture Creation

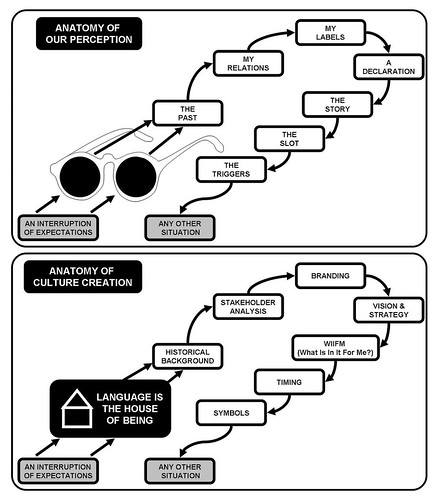

In the drawing below and the table I have taken the anatomy of our perception and created seven matching steps that are necessary for creating a new organizational culture.

Working on these seven components, all at the same time ensures a shift on the level of ‘being’ of the organization by setting a new context in which different things are possible.

Audit your “ROC” – Return On Communications

All of these elements (not necessarily in that order) constitute the key points of an organizational culture. This is what you need to monitor during the complete life-cycle of any change program. A successful communication strategy during organizational change takes into account the anatomy of our perception and works towards a similar mechanism in order to create a new culture.

Eventually, when scanning through your communication plan, all of these steps should be catered for; either in communication principles or in concrete actions. More important, this should also work the other way around: if you identify any communication action that does not accomplish any of the seven steps above, you should seriously question its added value for the program and the return on investment of attention, time, and money (exactly in that ranking order of scarcity).

__________________________

Sources used in this article:

Goss, T.: The Last Word on Power: Executive Re-Invention for Leaders Who Must Make The Impossible Happen, Currency: Doubleday. 1996

Weick, K.: Sensemaking in Organizations (Foundations for Organizational Science), Thousand Oaks: Sage Pubications. 1995

Pingback: Luc’s Thoughts on Organizational Change » Blog Archive » What about Chris Argyris?()

Pingback: Luc’s Thoughts on Organizational Change » The Chameleon Law()