There are four types of commitment in every community; they differ in terms of authenticity and collaboration. Having clarity on the four types of commitment helps us to see the universal energy flow of every community, the two places the flow can be broken and what we can do to restore the flow of energy in a community.

I used to think that commitment in a group is a behavior that is recognizable at face value: either people collaborate or they oppose an initiative. We tend to believe that commitment and resistance are easily observable. But there is more than meets the eye, because what really matters is whether the behavior you observe is authentic or not.

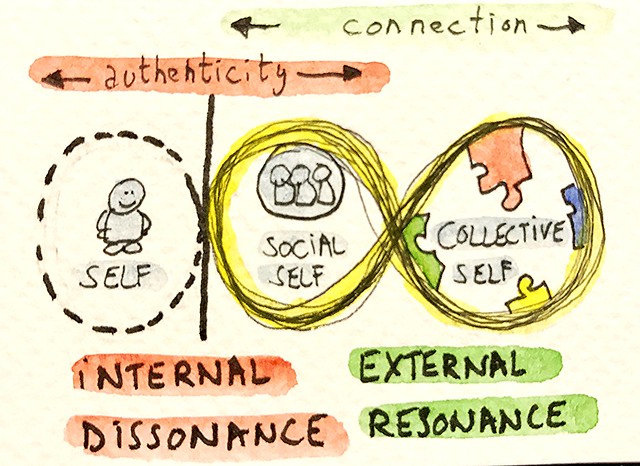

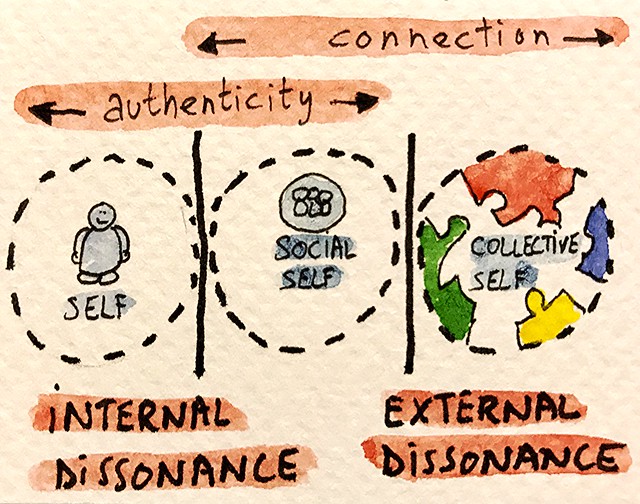

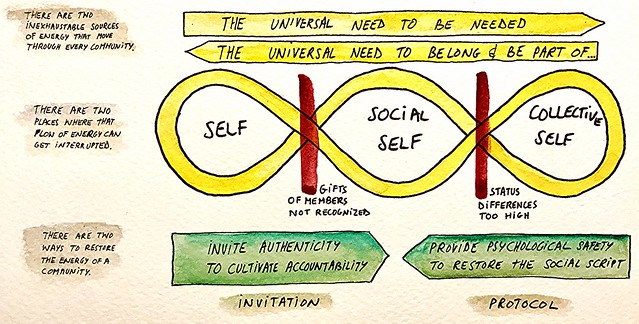

Remember the model that we presented in the previous article, where we underscored how the Self (who we are), the Social Self (how we show up) and the Collective Self (our collective potential) are linked. Our identity is shaped by the communities we are actively part of, and our ability for connectedness with other communities gets shaped by this identity in turn. If all goes well, the ongoing iteration results in a resonance of the three levels; a constant interplay of altering and sense-making.

But it turns out that this ideal flow of energy is not always working. Sometimes the flow gets interrupted and people get into trouble. In this article we will try to articulate what kind of trouble people can end up in and how we can make sure they get out of that trouble.

Authenticity is Key

Authenticity is the resonance between who we are (the Self) and how we show up (our Social Self). Without it we don’t have a framework to hold our-‘Self’ accountable, and accountability is what we need to build Social Architecture. The authenticity of a behavior is something we can sense or pick up easily in any interaction, both: digital or in real life.

- When there is internal resonance between who I am and how I show up, my behavior is authentic and I am accountable for what I contribute to a community.

- When there is internal dissonance between who I am and how I show up, my behavior is inauthentic, and this is draining energy from myself and the people around me.

The interesting part is that we need community to be fully authentic. Here is why: when you take apart the elements of what makes a person authentic you will end up with three parts:

- Who you are

- What you are here for (your purpose)

- What you are truly unique at (your gifts)

But the last part (your gifts) only becomes visible to yourself when you put yourself out there. The discovery of what we are truly unique at begins at the edges of our comfort zone and in interaction with the world. So authenticity only makes sense in a social context, because this is where it gets articulated.

Building a Diagnostic

Things get more real and our responses can become more effective when looking at the resonance between the Self (who we are), the Social Self (how we show up) and the Collective Self (the potential of our community):

- Authenticity or personal intent is all about the Self and the relationships we have built with our inner layers. How well are we internally wired and aware of who we really are, what we are here for and what we are truly unique at?

- Collaboration on the other hand is all about the Social Self and how our behavior resonates with the potential of a community (the Collective Self).

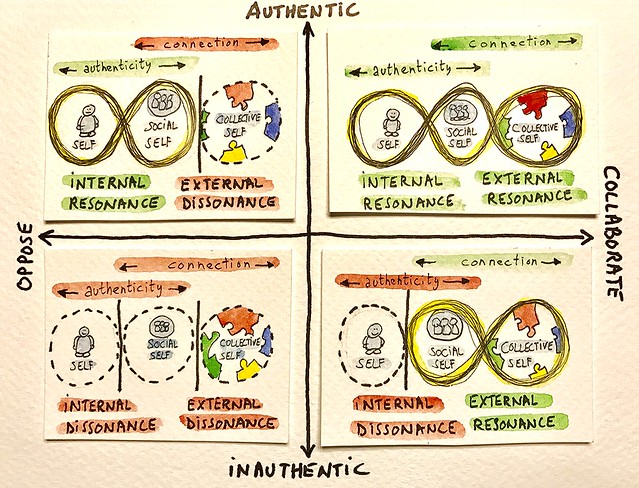

Let’s take a closer look. In the drawing below, the vertical axis displays Authenticity and the horizontal axis shows the level of Collaboration. As a result there are four quadrants:

1) Commitment

What happens when our intention is authentic and there are no restrictions in the context for us to behave accordingly. What we see is a full alignment between the Self, the Social Self and the Collective Self:

- Internal Resonance: the inner alignment between ‘who we are’ and ‘how we show up’ is called authenticity

- External Resonance: the external alignment between ‘how we show up’ and the intent of the community is called connection.

2) Resistance

Think about the common types of resistance that can be ticked in a check-box. Typical examples include: Need more detail, Giving a lot of detail, Not enough time, Impracticality, Confusion, Silence, Moralizing and Pressing for solutions (taken from: Peter Block – Flawless Consulting).

The point is that these behaviors demonstrate a ‘no’, but it is an authentic ‘no’. This is what we are witnessing on the level of alignment of the Self:

- Internal resonance: People are staying true to their inner Self and have the courage to be vocal about it in how they behave on the level of their Social Self.

- External dissonance: Courage is the right word to use here, because rather than staying out of trouble and fitting into what the social script of the community dictates, these people search for a way to express their concerns about the disconnect.

Every person has a different way give expression to the dissonance they feel between their true Self and the social script of a group, but in essence we should try to see it for what it is: a courageous attempt for reaching resonance between the inner world and the outer world.

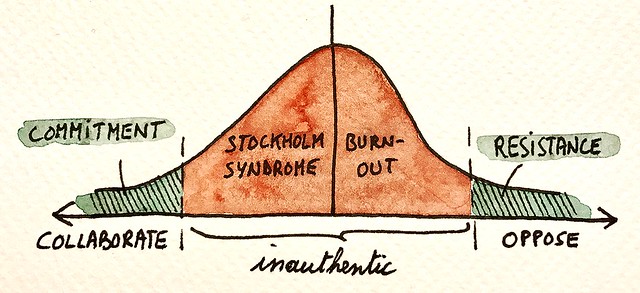

Both, commitment and resistance are authentic: how people show up is in sync with who they are. It takes maturity and courage behave in sync with your true Self when the social pressure to conform is high. This is why the quadrants of commitment and resistance are seldom crowded.

Both spaces require a great deal of vulnerability and courage. It gets more crowded when we look at the places where there is a disconnect between the Self, Social Self and the Collective Self.

3) Stockholm Syndrome

The Stockholm Syndrome – also known as ‘capture-bonding’ – describes the behavior of hostages who become sympathetic to their hostage-takers. The name is derived from a 1973 hostage incident in Stockholm, when several victims began to identify with their hostage-takers as a coping strategy.

It is the same kind of fear of repercussions that we can find in some organizations. People lose their sense of Self as if they were in a hostage situation and start to behave against their unwilling intent. From the outside they gladly collaborate and commit to the social script of the group, so their behavior is a false ‘yes’. Here is what is going on under the surface:

- Internal dissonance: There is a disconnect between what people really want – their true Self – and how they show up; their Social Self comes across as inauthentic.

- External resonance: How people show up looks like commitment from the outside. Often this is the best way for people to stay out of trouble and people will go a long way into fooling themselves that this is what they truly want.

This occurs in organizations where the social pressure to conform and the emphasis on control is high. And the return for this behavior is high, which explains why this quadrant is so crowded:

- For leaders this is a comfort zone of control and predictability. Traditional forms of authority do well with this type of commitment.

- This is also a comfort zone of innocence for many employees and community members, because as long as everyone tries to fit into the social norm, no one can’t be blamed when things go wrong.

The price we pay for this type of commitment is that the potential of the Self remains underutilized because it is disconnected from the world. The lack of authenticity results into a lack of accountability.

4) Burn-out

If we stay long enough in the comfort zone of the Stockholm Syndrome we will become convinced that we don’t have the resources to do things, or even think things, for ourselves. This is why, when we move to an environment where the social script of the Collective Self does appeal to our inner Self, we feel trapped. Trapped by the limits of a Social Self that we have been constructing over time and that turns out to be inauthentic.

This quadrant describes people with a good intention who are somehow hindered to follow their will because they are paralyzed by opinions and politics. On the level of resonance this is what we are looking at:

- Internal Dissonance: there is a disconnect between the personal intent and the way people show up. This loss of authenticity strengthens their belief that they are incapable of pursuing or accomplishing what they believe in.

- External Dissonance: from the outside their response looks like opposition or indifference, but in fact, what we are witnessing is a false ‘no’.

Burn-out begins as soon as we oppose something we desire deep inside. Over time we have constructed a facade that does not represent who we are (often because it was unsafe to be our-‘Self’). And when the opportunity is created to rise to the occasion, we feel locked-up by a Social Self that is neither authentic with who we are, nor connecting with the collective potential. This awkward tension is unbearable and will eventually lead to burn-out.

How bad is it?

Commitment, Resistance, Stockholm Syndrome and Burn-out; they are different levels of the same thing, when we look through the lenses of authenticity (internal resonance) and collaboration (external resonance).

Sadly, the inauthentic quadrants represent the majority of the populations we meet in an organizational context. Here is a very unscientific estimate of what the situation looks like in most organizations:

We don’t want to make a judgement about how bad it is for those who live in the inauthentic quadrants, because the return for not being authentic is that you don’t have to be accountable either. In short: it’s a personal choice.

What we are interested in are the types of commitment that unlock the potential of a community and what we can do to leverage this process. This is where the insights of the Self and the Social Self are useful, because they depict exactly where the disconnects occur.

The Paradox of Accountability

Everyone is here for their version of “Why”. We all have a universal hunger to be needed and when we find a community that genuinely responds to that need we tap into an inexhaustible source of energy within ourselves. To quote the Dalai Lama in a recent article:

Being “needed” does not entail selfish pride or unhealthy attachment to the worldly esteem of others. Rather, it consists of a natural human hunger to serve our fellow men and women. As the 13th-century Buddhist sages taught, “If one lights a fire for others, it will also brighten one’s own way.”

Belonging occurs when we tell others what gifts we received. When that happens in the present moment community is built. Here is what it takes to restore the disconnect of authenticity:

First of all, a personal commitment to be accountable for appreciating the gifts in others. We need community to discover what we are truly unique at. When we construct our Social Self on the unique gifts we have to offer we can be a producer, a helper and find dignity.

Second, when we are in a position of authority we have a special opportunity to invite the authenticity in the people around us. We attach a specific meaning to invitation,i.e.: that we are constantly looking for opportunities to offer people a choice, so that every time people opt in, they are here by choice.

The fact that refusal is possible makes a participation valuable. This is the paradox of accountability. Our job is to make explicit that refusal carries no cost. This builds a framework for people to become accountable for how they show up. If one decides to be here by choice they will make sure their Social Self represents who they really are.

There is no point in being accountable for a Social Self that isn’t you, right?… this is a pathology that we have earlier referred to as the Stockholm Syndrome. And this brings us to a second disconnect, which is all about the question: is it safe enough for people to be who they really are?

The Paradox of Protocol

Accountability is one thing, but when the social pressure of context is high on command an control the status differences are so high that genuine communication becomes rare and collaboration is reduced to compliance. In other words: we are blocking a climate in which people feel free to express relevant thoughts and feelings. This is called a lack of psychological safety and it can have serious consequences ranging from medical errors to defective launches of space crafts.

So how do we bring psychological safety back to groups? The research of HBS professor Amy Edmondson and MIT professor Edgar Schein relies on decades of evidence that all points in the same direction: in order to cultivate an environment of psychological safety, the focus should be on reducing cultural and status differences that are causing a paralyzing power-distance. In the below video we can see that Edmondson stresses the need for inclusive leadership which lowers the cost of speaking up.

This means that we intervene on the level of the protocol that makes it safe to connect with the Collective Self. With protocol we mean: being explicit about the language, the boundaries, the agreements, the roles, the group-rules, the scenario’s, the checklists, the rituals, the behaviors that are OK and those that are not; in other words: all the elements that determine the social script of a room.

Protocol offers protection when status differences are too high. It provides safety for the way we show up (the Social Self) and increases the chances that members of a community will start to contribute to the Collective Self. This is the paradox of protocol – a word that at first sight seems to signify ‘command and control’. There is one big disclaimer though: protocol only works when it is established through legitimate authority; i.e.: the inclusive leadership that Edmondson talks about in the above video.

Making it Work

The best shot we have to restore or avoid disconnects of authenticity and connection is to work on personal accountability through invitation and psychological safety through protocol. But first we need to remind ourselves of the two inexhaustible sources of energy that make every community tick; they are:

- The universal need to be needed

- The universal need to belong

The only way to tap into the potential of the most underutilized resources of an organization is to pay attention to keep that movement going:

An ongoing flow between who we are, how we show up and what we contribute to the collective. The iterations are at least as important as the establishment of the links. Reaching resonance is an ongoing process.

But more often than not, the flow gets interrupted on two specific places:

- gifts of members go unrecognized

- status differences are too high

In order to restore it we need to invite authenticity of the members so they have framework to become accountable. At the same time we need to provide psychological safety in order to restore the social script of the community. There is no better way to summarize what the true work of a Social Architect consists of: cultivating accountability and providing psychological safety.