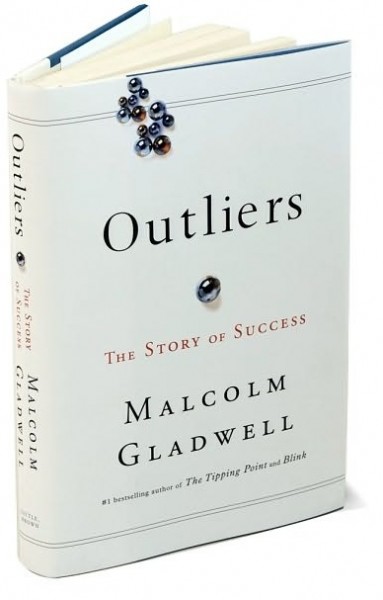

by Malcolm Gladwell

In Outliers: The Story of Success Gladwell offers a remarkable perspective on success. In our mind success is solely the result of personal achievement, persistence and intelligence. Apparently, that is only half the story.

Did you know that the month of birth largely determines the success rate of ice hockey and soccer players? Did you know that Bill Gates and other silicon valley tycoons were actually lucky to be born in the the same time-slot?

Opportunity and legacy seem to be the two major factors we disregard when we make sense of success.

Gladwell goes a long way to analyze their history and concludes that intelligence and talent are one thing, but opportunity and legacy are the major factors determining whether the talent and intelligence are fertilized or squandered.

Opportunity is what Bill Gates has in common with The Beatles. Of course they were talented, but without the opportunity of unprecedented access to a computer on the one hand, and Hamburg 8-hour long gigs where they got stage-opportunity on the other hand, they would have been an anonymous programmer and a mediocre band.

Even more intriguing is the role of legacy and culture as a factor determining success. In his fascinating story-telling style Gladwell gives us a different perspective on the Eastern European Jewish immigrants in 20th-century New York, the Asian math wonders and even his own Jamaican roots. Did you know that Asian math wonders are more likely to be related to the persistence that is required to cultivate rice as it has been done in East Asia for thousands of years, than any other genetic or linguistic cause? Now that is fascinating!

Gladwell continues to compare high-IQ failure named Chris Langan with the brilliantly successful Robert Oppenheimer and finds that the presence or lack of entitlement is the legacy that caused Langan to fail and Oppenheimer to succeed (note: Oppenheimer developed the first nuclear weapons). Entitlement is the learned behavior that marks the difference between successful children and non-succesful children during their schoolyears and pretty much the rest of their lives. Gladwell concludes that success has a predictable path. When we misunderstand the real course of success we squander talent.

Personally I find the chapter ‘The Ethnic theory of Plane Crashes’ the most intriguing. Gladwell dives deep into the investigations of plane crashes of Korean Air, Avianca and Florida Air and zeroes in on the cockpit transcripts. He analyses the dialogues between the crew and the traffic controllers with the help of Hofstede’s culture dimensions (PDI – Power Distance Index) and finds that when we ignore culture, airplanes crash.

A Colombian crew lacking the direct language to address the over-assertive JFK traffic controllers causes the Avianca 052 plane to crash simply by running out of fuel: 73 fatalities. The power distance between the captain and the co-pilot of Florida Air results in the co-pilot to using indirect language (‘mitigated speech’) to address too much ice on the wings: 78 fatalities. The subtle language that is engrained in Korean culture hinders the co-pilot of Korean Air to speak up and to invalidate the captains judgement: 228 fatalities.

Although we probably cannot underscore Gladwell’s theory with scientific evidence, this book is an eye-opener.