The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

A Black Swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics:

1. It is unpredictable;

2. It carries a massive impact;

3. After it happend we construct an explanation that makes it appear less random and more predictable than it was.

The success of Google and 9/11 are two examples of Black Swans. This book examines why we only acknowledge Black Swans until after they occur. Nassim Nicholas Taleb explains in great detail the denial mechanisms of our mind and how they are embedded in our society. The basic message of this book is that reality is more brutal and groundless than our minds are capable of imagining. Our minds can explain and predict far less than we want to acknowledge.

Taleb does a great job in painting the image of Mediocristan and Extremistan to make his case.

FIVE concepts that I will remember:

- Platonicity or the error of confirmation : this is the tendency to mistake the map for the territory by looking for instances that confirm our beliefs. Human beings have a need for categorizing reality and then tunneling around those categories;

- The narrative fallacy: the fact that stories stick to a far greater extent than ideas. We are adicted to causality and we have an unstoppable desire to glue reality together with ‘because’;

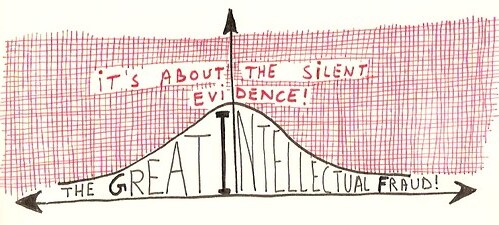

- The problem of silent evidence: What we see is not necessarily all that is there. History hides the odds of some events;

- The GIF (Great Intellectual Fraud): this is Taleb’s nickname for the Gaussian bell curve.

- In the province of Mediocristan the laws of nature are Gaussian and particular events don’t make a difference individually, only collectively. In Extremistan a single observation can impact the total significantly. The point is that we live more often in Extremistan than not.

TEN interesting quotes that I will take away from this book :

Our minds are wonderful explanation machines, capable of making sense out of almost anything, capable of mounting explanations for all manner of phenomena, and generally incapable of accepting the idea of unpredictability.

History and societies do not crawl. They make jumps. They go from fracture to fracture, with a few vibrations in between. Yet we like to believe in the predictable, small incremental progression.

Categorizing is necessary for humans, but it becomes pathological when the category is seen as definitive, preventing people from considering the fuzziness of boundaries, let alone revising their categories.

The narrative fallacy addreses our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an explanation into them. Explanations bind facts together. They make them all the more easily remembered; they help them make more sense.

From an anatomical perspective, it is impossible for our brain to see anything in raw form, without some interpretation.

We are too brainwashed by notions of causality and we think that it is smarter to say because than to accept randomness.

My biggest problem with the educational system lies precicely in that it forces students to squeeze explanations out of subject matters and shames them for withholding judgement, for uttering the ‘I don’t know’.

Alas we are not manufactured, in our current edition of the human race, to understand abstract matters – we need context. Randomness and uncertainty are abstractions.

The Gaussian bell curve sucks the randomness out of life – which is why it is popular. We like it because it allows certainties!

I noticed that very intelligent and informed persons were at no advantage over cabdrivers. Cabdrivers did not believe that they understood as much as learned people – really, they were not the experts and they knew it. Nobody knew anything, but the elite thinkers thought they knew more than the rest because they were elite thinkers.

One final note: although the author’s erudite style of writing results in longs sentences and pages of intellectual masturbation, I encourage readers to push through and not get hooked by this arrogance. The message of this book is just too important.