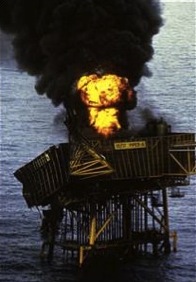

The “burning platform” story has become a permanent part of the organizational change landscape. In this series, our guest author Daryl Conner offers some background about how he found and introduced the story, what its original purpose was, how that intention has sometimes been misunderstood, and some of the implications for change practitioners who incorporate the metaphor into their practice.

As I described earlier in this series of posts, what drove my original interest in the Piper Alpha event was my desire to find a metaphor to reflect the commitment needed to sustain movement away from unacceptable conditions. The burning-platform story is about the level of resolve it takes to break from the past and counter the inertia that holds people inside their zone of familiarity.

The pain associated with the way things are, however, is not the only motivation for organizational transformation. The costly nature of existing circumstances addresses only half of the formula needed for people and organizations fully realize fundamental change.

Pain and Hope are Constant Companions on the Journey

Kurt Lewin was the first to popularize the fact that there are duel forces involved in change. In the 1940s, he said the present state has to be “unfrozen,” transformed, and then “refrozen” before fundamental change can emerge. What happened to Andy is nothing more than an elaboration on his brilliant insight into the process. He, of course, made no mention of a burning platform, but his views did include the notion that it is the pain of the status quo that thaws the fixed (frozen) ways people and organizations are fixed in their routines and habits.

Kurt Lewin was the first to popularize the fact that there are duel forces involved in change. In the 1940s, he said the present state has to be “unfrozen,” transformed, and then “refrozen” before fundamental change can emerge. What happened to Andy is nothing more than an elaboration on his brilliant insight into the process. He, of course, made no mention of a burning platform, but his views did include the notion that it is the pain of the status quo that thaws the fixed (frozen) ways people and organizations are fixed in their routines and habits.

In addition to the unfreezing (pain) part of his model, Lewin also suggested that a refreezing motivation is essential to promote consolidation around a new alternative. Attraction to a new future provides hope that there can be a more positive outcome than the one to which existing circumstances point.

As practitioners, we must remember that orchestrating sustained transformations involves helping clients leverage both pain and hope. The pain associated with maintaining present circumstances and the hope for a brighter future fuel the engine of deep, sustainable change. This means that pain management and viable solutions are fundamental aspects to change architecture.

Proper development and application of pain management (PM) is central to the change facilitator’s role. Although the transition process has its hardships, that’s not the discomfort I’m referring to here. Instead, I am speaking to the pain associated with not changing that is so important to transformational change. PM is the deployment of carefully crafted sponsor communications and appropriately applied consequences to help people understand that the price for the status quo is prohibitively high.

Often, leaders are aware of the risk of maintaining the current state long before the rest of the organization. When this happens, deciding that a change is necessary is the easy part. The challenge is convincing an entire organization of the necessity to stop or lessen their reliance on many of the routines and frames of reference to which they have become accustomed.

Once people understand that what they have been doing is no longer a reliable option, there is usually a greater openness to exploring alternatives. This is when leaders’ solutions can gain some traction. Trying to convince people of the benefits of a new future when they are satisfied with what they have is not a path to change success. On the other hand, persuading people that what they have is no longer feasible but failing to offer any hope for a better alternative creates ulcers, not change.

Introducing viable solutions (VS) is the second key element to change architecture. VS are offered by deploying communications and consequences designed to foster the view that the change is both preferable and within reach. Solutions are viewed as viable only if they are seen as both attractive (relative to the status quo) and accessible (understandable, affordable, etc.).

The pain associated with the present state (PM) and the hope generated by a practical alternative (VS) are both necessary to create the needed commitment to sustain transformational change. They are equally important to achieving realization, yet each carries a disproportionate weight of influence at various times in the implementation process. For example, there is a need for greater emphasis on PM in the early stages of an implementation effort…not because it is ultimately more important than VS but because it is typically more neglected at the beginning.

Many organizations are comfortable promoting the benefits of the desired state, but because they are afraid of appearing too negative, they hesitate to engage in explicit PM communications and consequences. The result is that people hear about a solution (the change) to a problem that, from their perspective, doesn’t exist or is only a minor concern.

Because of the frequency with which organizations fail to properly engage PM, let’s examine what is behind this reluctance. In particular, I’d like to explore whether we as change practitioners sometimes contribute to this hesitancy.

The Practitioner’s Influence

Of course, people are capable of shifting toward attractive new things during incremental change, but the focus here is on substantial transitions, not continuous improvement. The small adjustments we make in life are fairly easy to complete. When we embark on the big endeavors, however, we can become easily distracted. Why is this the case?

In general, I have found that clients have a harder time sustaining major shifts if the only purpose behind their initiatives is to accomplish something desired, instead of also relieving the burden of something dreaded. It is not difficult to start a major change based on a yearning for something new, but if that’s the only, or even the primary, motivation, the odds of staying the course are less than if a problem is also being solved.

I realize many practitioners wish this weren’t the case. In fact, some will consider me “politically correct” for saying people won’t likely change something fundamental just because they want to enjoy a new advantage. My response to those with this view is that when I examine my four decades of change facilitation experience, I can’t identify a single case where successful major initiatives were executed that didn’t include some elements of pain as well as hope. It is both the avoidance of the cost of the status quo, and the desire for a new potential benefit that drives transformational change. I want to be clear—I’m not suggesting pain is the only motivator in play. I’m saying that without an expensive status quo, the cost of transformation is unlikely to be paid.

What I believe this means for us as practitioners is that we should operate on the basis that a well-crafted PM strategy is vital to:

- helping leaders confirm and express their own resolve toward change and,

- enrolling others down in the organization to invest the same level of commitment.

Our role puts us at the forefront of either fostering or impeding the explicit use of PM by leaders, so our own acceptance or rejection of the need for PM is pivotal. This leads to a crucial question for each of us to ponder: Is it essential for people to believe the price for the status quo is too high before the organization can fully realize major change? Our respective views on this issue have an important bearing on our effectiveness so I invite you to give this some thought.

My response to the question is a resounding YES.

My bias is probably evident at this point, but I’ll summarize it. My years in the change business have shown me that, most of the time, most people fail to reach (much less sustain) their intended outcomes when they are driven solely or even primarily by wanting to exploit the opportunities before them. It’s not hard to engage these kinds of projects, but, more often than not, they fall to the wayside before reaching realization. Therefore, sponsors need to ensure a well-thought-out PM campaign is included in their implementation architecture. Without such a view, it will be much more difficult for people throughout the organization to buy into seeing change as a burning platform/business imperative instead of just another set of good ideas that may or may not reach their stated objectives. Subsequently, I believe as professional change facilitators, it is our responsibility to advocate for, help design, and skillfully orchestrate effective PM strategies when we are engaged in crafting execution architecture for our clients.

What to Emphasize, and When

As professional change facilitators, our primary focus isn’t the what of change, it’s the how. Our contribution to an organization’s success is tied more to enabling execution than it is to shaping the content of the changes being pursued. In this light, when we develop implementation architecture, we’re not creating pain and hope, we are helping clients uncover, articulate, and leverage the pain and hope inherent in what they want to accomplish.

As stated above, when introducing dramatic change, it is important to describe why people need to depart from what they have been doing, as well as to provide a compelling picture of what they should move toward. However, during the initial phases of implementation, it’s essential to place a disproportionate emphasis on the PM perspective.

Here’s why. Most projects begin during uninformed optimism and then fall into the depths of informed pessimism. Once people reach their tolerance for ambiguity and loss of control, change is no longer fun and the tendency is to push back against it. This penchant for resisting is so strong that, as a species, we will consistently choose familiar states, even if they are not working well (relationships, organizational structures, etc.) over something new. We do so in order to maintain the sense of equilibrium that comes with sticking with what is predictable in our lives…our established habits and routines. PM is critical to emphasize early on, when people are first hearing about change, because otherwise their commitment to shifting things will be too casual (good ideas). Instead, what’s needed during major change is a cathartic-level resolve that carries enough emotional punch to break from old patterns (business imperatives).

Both PM and VS should be reflected in communications and consequences throughout the change process; however, early on, PM should take center stage. VS is what promotes the case for moving forward but PM creates a reason to listen to and be interested in VS. In addition, PM reduces the inevitable pleas for returning to what was when the journey becomes harder than people expected.

Think of PM and VS as two ends of a continuum where each is strongest at its respective pole, while being more evenly balanced in the middle. Once the bond to the existing state is weakened by PM, it is time to strengthen the emphasis on the VS. This is not, however, at the expense of PM. As the implementation process matures and ground is gained toward the desired state, there should simply be more weight placed on VS, not less on PM. Once well into the execution, where critical mass of commitment has been reached and there is little chance of losing momentum, PM can be de-emphasized with a stronger focus being placed on VS.

There is much to be explored about how VS is used to foster hope during the change process. However, the focus of this series is on the burning-platform story. We’re looking at how it can be used as part of crafting a PM strategy that fosters the commitment to break free of the pull of the status quo. We’ll examine some of the implications related to the proper use of VS at another time.

In my next post, I will cover some implications for practitioners wishing to use the burning-platform metaphor.