In this article I want to focus on 10 questions that will help us to get serious again about learning, because 99% of what ‘learning’ really is occurs outside of the classroom.

Yet, we still find ourselves training and being damn good at the coordination of that activity. But did learning ever occur on that path? We will never know if we don’t ask the right questions.

Learning versus Training

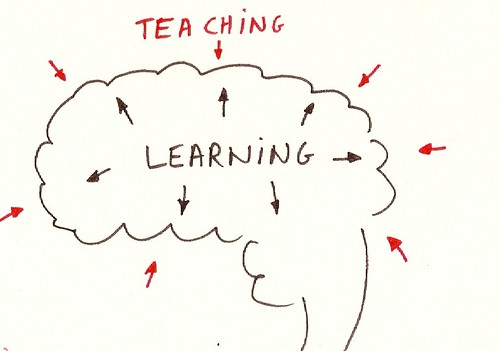

Learning is a different activity than training. In fact, it is the opposite of training or teaching. Learning is what we automatically do when our attention is triggered by something: a task, a need, an urgency or a serendipity. Learning is an inside-out process; and since it is what we do by design it does not cost us any effort. It’s natural.

Teaching or training on the other hand is the opposite movement. It is the transfer of knowledge from the outside to the inside. More often than not it is followed by fatigue, exhaustion or saturation. It takes some effort.

Strange enough, teaching and training have become the norm when we talk about ‘learning’ in general. It’s a habit we have inherited from several generations of succesful economic growth.

Over the past 125 years (the Industrial Revolution) our complete education system has been based on the premise that we need to train workers to perform in factories. Command-and-control was the slogan that would create economic growth. And it did. Without any doubt, our economy, our society and our well-being would not have progressed to the current levels of prosperity without compliance and obedience. But as we know, the traditional economy is grinding to a halt. What got us here won’t get us any further.

Unfortunately, training is still considered as the only way for learning to occur, even though the old economy stopped being productive long time ago. So it’s time to question our beliefs about learning that we have taken for granted over the past 125 years.

A Flashback

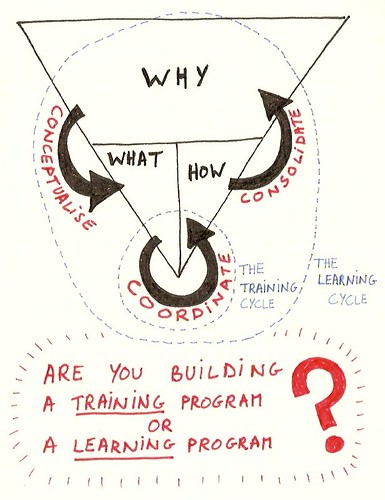

In a previous article on learning I have underscored the importance of the learning cycle for organizations. My point was that we should not just focus on the coordination of explicit training, but rather look at the bigger picture of tacit knowledge. This involves not only the trainer and the learner, but sheds a different light on the responsibility of the hierarchical superior who ordered the training in the first place. The frame of reference I use to talk about learning is the one I have built throughout the previous article. Here is a condensed summary of that article:

It is very easy for us to think that all knowledge is in the head, but we often ignore how much of our knowledge exists in action, participation with the world, participation with the problem and participation with other people, i.e., practices.

The three ingredients of learning are Motivation (the emotional stuff below the surface), Knowledge and Skills. They determine the domain of action for making the learning happen.

99% of what ‘Learning’ really is occurs outside of the classroom. That’s why we need to focus on the learning cycle as the larger context of training programs. The different wording is essential, because when I say “Learning”:

– I mean training coordination PLUS all the stuff that happens before and after: conceptualizing and consolidating;

– I mean participants PLUS their bosses;

– I mean the how, underscored by the ‘what’ AND propelled by the ‘why’;

– I mean training execution PLUS a learning relationship between participant, leader and trainer.

I made a distinction between the training cycle (the lower part) and the learning cycle (the whole) as shown below:

The main frustration here is that the knowledge provided during training is so theoretical that it has nothing in common with practice. Many people have had the ‘what’ and the ‘how‘ pushed down their throats. But the project grinds to a halt soon after that because people have not been given the time to participate and make sense of it all (the underlying ‘why’).

The inevitable truth is that people will need to tinker with the ‘why’ anyway in order for the program to work, so it is better to do that during preparation than to pay for it in terms of a sputtering go-live. That is why it is necessary to effectively involve them before, during and after the training.

Ten Questions

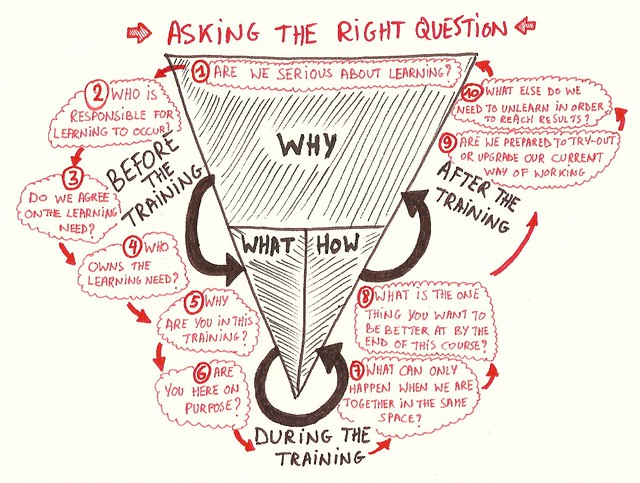

So after that extremely long introduction, here is what I really wanted to say. If we are serious about learning and if we don’t want to mistake it for training (as in: ‘training a dog some new tricks’) – we need to ask ourselves 10 questions that relate to the before, during and after-part of a training.

Let’s have a look at them one by one:

- Are we serious about learning?

In other words: what are we committed to? The compliance of the organization, or the potential for co-creation that occurs in its communities? In a world where change is accelerating and innovation is becoming more important, we need more than the compliance that got us here. Today, value creation is driven by higher order human capabilities of initiative, imagination and passion. Being serious about learning means that you are prepared to trade compliance for co-creation when it comes to setting up a learning program. If not, then don’t continue to the next question – it’s ‘game over’. - Who is responsible for the learning to occur?

In the old world this is a simple question to answer. When a worker is not performing well, send him to a training and never question your own management skills. If we are serious about learning, we ask ourselves what is blocking the worker from performing well. It takes courage to ask that question. - Do we agree on the learning need?

Another tough question to ask. Training is the path of least resistance, i.e.: the easy way out if we want to hide a tougher problem. The truth is that the majority of in-house trainings are set up so we don’t have to address the real problem at hand: a management problem, instead of a knowledge-gap. - Who owns the learning need?

To cut this one short: I am so tired of having ill-informed and resistant participants in the room, just because their boss is shying away from the real problem (either: a lack of authority, or a control neurosis). If the boss does not own the problem or the learning need, it will be impossible to consolidate anything after the training. It’s a loss of money and a disrespect to the participants. - Why are you in this training?

This question should take up the first part of your training course. If people cannot articulate why they are there, you should help them to do so. Granted, most of them will tell you that their boss sent them, but still they came, so now that they are here, why not pick something to take with them at the end of the day? The point is that people should be hungry for something before you start. - Are you here on purpose?

This is not the same as the previous question. Being there on purpose means that you offer the people the opportunity to think it over during the first break and only come back in when it is a deliberate choice. Yes, this puts you at risk as a trainer – and that’s the whole point. If you are serious about learning, you are in it together: the participant and you. - What can only happen when we are together in the same space?

Training is an opportunity to have people in the same room for a longer stretch of time, in order to focus on a certain topic. Trainers should be aware of this unique opportunity and focus on what is uniquely possible when people are together in the same room. Big surprise: it’s not the transfer of knowledge, but the sense making of the context and the building of community based on commonalities. Another reason to stop teaching and start facilitating. - What is the one thing you want to be better at by the end of this course?

People may be attending because their boss told them to, but we need to kindle their responsibility for learning. As a participant, they are responsible to get what they need out of this training by asking the right questions. - Are we prepared to try-out or upgrade our current way of working?

This refers to the fragile cut over to the reality of the working place. We can predict the result by asking the first three questions. Both, the participant and the boss should realize that the results of the training will require them to create some pull in the working context as well. If not, better forget about it. - What else do we need to unlearn in order to reach results?

Come to think of it, this places the responsibility again with the team of the participant. This is not a co-incidence, since real knowledge resides in the social fabric of a team, not in a book , a head or a training course.

The Shift from Content & Collection to Context & Connection

Asking these 10 questions over and over for each training we organize or attend will redirect our attention to what really matters when it comes to learning and we may be inclined to radically change our approach for the better. Some examples of what you may find yourself doing when you run over the checklist on a regular basis:

- Share all the content of your training with the participants before the training. That way, the time spent during the training can be optimized to discuss real issues and to make sense of the content within the context of the participants. It’s not about the slides. At best those slides contain 10% of what a participant needs in order to perform his job in practice. The last 90% is situated in the field: in the middle of conflicts and problems. This is what we should make sense of when we are together.

- Stop teaching, start facilitating. As a trainer, my task is to ask the right questions and then to frame the answers that I receive. So I will not be standing in front too much of the time. Rather, I will be standing behind the participants to motivate them to come up with those answers.

- Reduce your content with 50% and make place for participants to contribute the other 50%. It’s time for trainers to realize that they are not the smartest people in the room. Their role is to hold the space for the participants knowledge to be shared and for the participants to connect.

- Stop thinking that the above suggestions are radical and over-the-top. All I am doing is reshaping some stuff we have taken for granted to the natural process we are designed for: learning.

Pingback: Education 3.0 | Reply-MC()